When the historic Oakland Education Association (OEA) strike ended in early March 2019, school nurses Sarah Nielsen Boyd and Stephanie Lim were angry. They and the other 19 school nurses tasked with the health needs of 37,000 Oakland students had walked picket lines for seven days for the schools their students deserve, but when the agreement called for new bonuses and stipends to attract and retain school nurses, they felt their needs for more resources to help with untenable workloads were unaddressed. And worse, they felt misunderstood.

Images of the proud, defiant school nurses and their homemade signs with jaw-dropping student ratios flooded social media and news reports during the strike. And when OEA’s bargaining team reached a historic tentative agreement, they had won retention bonuses for school nurses of $10,000 for the current and next year, as well as an additional 9 percent by 2020-21 on top of all negotiated salary increases (more than 20 percent total). But Boyd, Lim and their fellow school nurses were devastated.

“We didn’t want a bonus,” Boyd says. “We wanted more resources for our students — a nurse in every school.”

Over the past five years, the number of school nurses in Oakland Unified School District had dwindled to the point where a third of the positions were unfilled heading into the strike. When longtime nurses retired or left for districts with supportive administrators and better resources, OUSD began dragging its feet on hiring new school nurses, Boyd says. Open school nurse positions went unposted at education job clearinghouse EdJoin, as district personnel administrators opted for unconventional locations to post their positions, according to Boyd and Lim. They say applicants — nurses who want to work in Oakland schools — would often not hear back about vacancies from OUSD.

“We started 2018 with 11 open positions,” Boyd says, noting that a lack of school nurses is an area where California falls way behind the rest of the country — 75 percent of schools nationally have a school nurse compared with only 43 percent in California, according to the National Association of School Nurses. “One of the good outcomes of the strike was that we were really seen and heard. And everyone knows we were really angry with the way it ended.”

Dissatisfaction is an opportunity

While vocally unhappy with the new contract, the school nurses didn’t stop organizing for the resources they need and their students deserve. Nurses and union leaders continued working on numerous workload-related grievances, including for caseloads far in excess of the 1,350-to-1 ratio set in the collective bargaining agreement.

In September 2018, five months before the strike, OUSD made a settlement offer with $2,000 in guaranteed stipends, senior nurse and longevity pay, and the hiring of three non-public-agency nurses for student diabetes management (OUSD has 70 students whose diabetes requires monitoring and management multiple times a day by credentialed school nurses who often have to travel between sites to perform these vital services). The nurses rejected the offer.

In the months following the strike, union leadership and OEA/CTA staff continued working to reach an agreement on these grievances. Unified by the strike, the nurses organized around their issues, working to educate their teaching peers on the gravity of their situation and building support among their fellow OEA members. Every single nurse was present during grievance conferences, and all participated in thorough discussions before responding to OUSD settlement proposals. They spoke with one voice, briefing OEA leadership on their message so that management always heard the same concerns and demands from the union, no matter who was speaking.

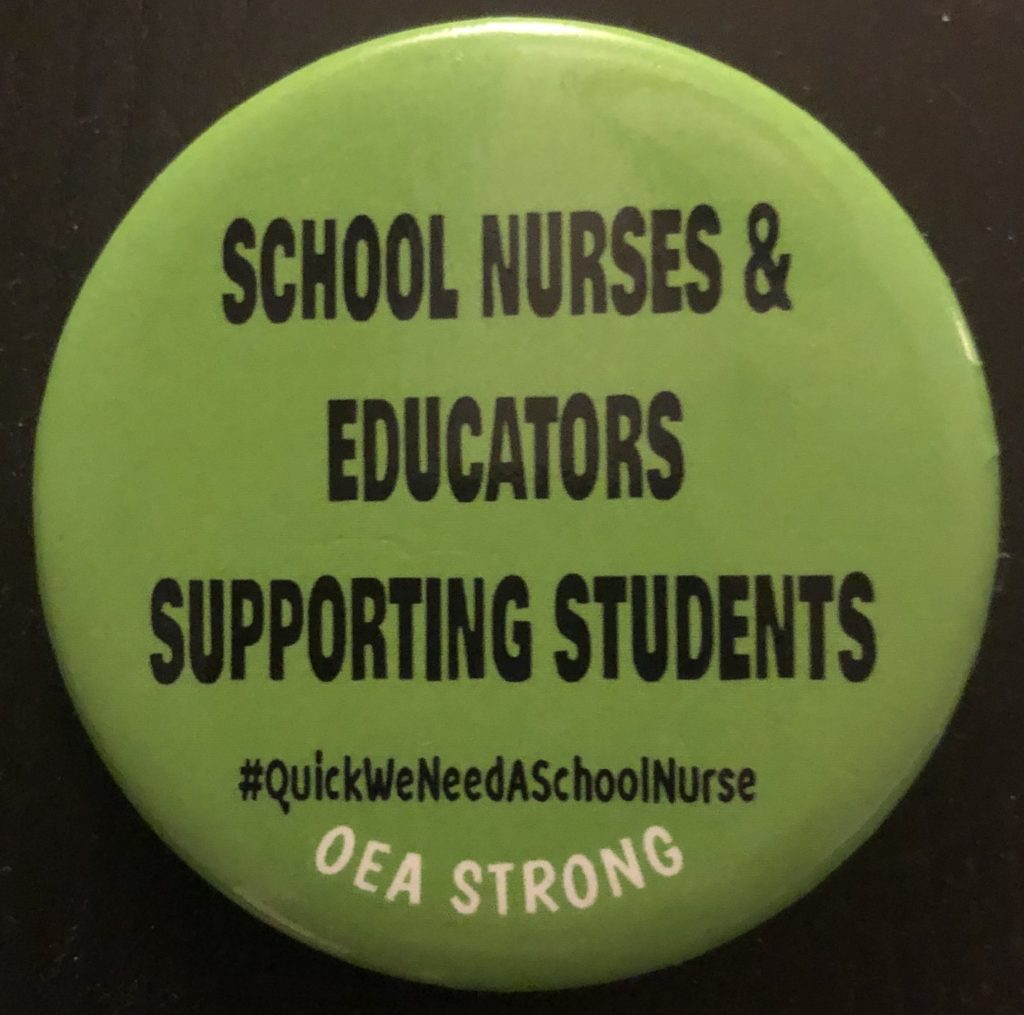

The nurses were fearless in their advocacy, identifying problems and demanding solutions from the district, even developing a campaign called “Quick! We Need a School Nurse!” to publicize the lack of health services for their students. They collected postcards with signatures from parents and teachers, delivering them to the OUSD school board to demand adequate resources and to shine a light on the continued failure of elected officials to address the health needs of Oakland students.

“The progress we’ve made here is due to our nurses taking the bull by the horns,” says OEA President Keith Brown. “Their tenacity has made them role models for our whole union. Now school psychologists and speech-language pathologists are uniting to enforce their contractual rights, too.”

The nurses’ efforts were fully supported by OEA leadership and staff, who worked closely on the settlement, while Brown reiterated their points during his regular meetings with the OUSD superintendent. The deep organizing work came to fruition in October when OEA won a massive settlement with $19,000 in guaranteed stipends for each school nurse, the establishment of a substitute nurse pool, and additional pay when caseloads exceed 1,350 students per nurse. Lim says the settlement is a step in the right direction to improving the services for Oakland students and working conditions for overworked and bedraggled nurses.

“On paper, they acknowledged we were over our heads,” Lim says, noting that the working conditions take a difficult toll on nurses who want to do what’s best for kids. “We want to care for everybody. It’s what’s inside of us. But then we don’t take care of ourselves.”

Boyd believes that every Oakland public school should have a school nurse, pointing to the California Association of School Nurses recommendation of one school nurse for every 750 healthy students. As of December 2019, there were 1,352 students per school nurse in Oakland — almost double the recommendation, but a substantial improvement from the 1,742-to-1 ratio nurses faced only a year prior. And while Boyd worries about OUSD’s sincerity in addressing issues raised by overworked nurses, all the school nurses, now 28 (“Our union meetings are a lot bigger,” she remarks), are organized and ready to advocate for the issues important to them as OEA prepares for the next contract.

“I want to be involved in bargaining,” Boyd says. “I want to start having conversations about our issues now. It was very clear to me that our needs were not fully understood.”

Advice for student support groups: Organize

Student support services, which is the umbrella term for all specialized services that employ speech-language pathologists, counselors, school psychologists and school nurses, have recently been centerpieces of struggles in California and across the country. Unions including OEA have bargained for lower caseloads and more resources for these groups. In order to advocate for the resources that reflect their unique needs, Boyd recommends that the groups become more visible in their local associations and their school communities.

“By nature, nurses are invisible,” Lim says, suggesting that student support groups work to provide a baseline education about what they do and how they help students. “So many people think a school nurse sits in her office and passes out Band-Aids, but that’s such a small part of what we do.”

Boyd encourages student support groups to build coalitions and identify issues they can organize around to grow their collective voice and advocate for what matters to them. With negotiations for the next Oakland contract just around the corner, Brown welcomes the continued activism of school nurses to fight for the resources their students need.

“Our students need smaller classes sizes, wrap-around services and a nurse at every school,” Brown says. “We hadn’t addressed nurses in our contract since 2002. That’s 17 years of missed opportunities. Our powerful strike and the nurses’ organizing have accomplished a lot, but there’s so much more we can do for our members, our students and our community. We’re all continuing the fight together.”

The Discussion 0 comments Post a Comment