Illustration by Audrey Chan

“The pandemic just exposed the gaps that have always been there,” says Terra Doby, a Richmond kindergarten teacher who is working in a new after-school tutoring intervention program for second through eighth grade. “I hope this is the beginning of the work our community and our students need.”

Throughout California and across the country, educators are stepping up to safely support students, their families and one another through the pandemic, working harder than ever to show that even though most classrooms are closed, the care and compassion have never stopped. Lauded as heroic during the initial months of distance learning, educators’ efforts have been overshadowed in recent months by growing concern about the ongoing impacts of COVID-19 and widespread lack of in-person instruction for a year now. Education “experts” have expressed this in a woefully oversimplified and deficiency-based term: “learning loss.”

Concerns about learning loss lead the nightly news today, with some politicians and parent groups weaponizing it to force teachers to return to schools before it is safe to do so.

Despite this narrative, educators have been focusing on supporting their students’ unique needs since the beginning of crisis distance learning. They’ve been working together to make connections, meet students where they are, make sure they feel seen and heard, and help them along their academic paths. It’s a part of the story that often gets left out when discussing studies about learning loss that are based on assessments we don’t use in California, have insufficient sample sizes, or aren’t representative of student populations and experiences.

“Learning loss is a calculation masquerading as a concept — a shallow, naive, ridiculous concept,” wrote math educator John Ewing in Forbes.

“We’ll need time to fill the gaps, but the kids are very resilient.”

—Yesenia Guerrero, Lennox Teachers Association

There’s no disagreement that every single student is being impacted by COVID-19 and there are resources available, so what can educators do to help mitigate those impacts? As part of last year’s COVID relief bill for schools (SB 98), all school districts were required to create Learning Continuity Plans outlining how they intend to support every student. This year’s school reopening legislation (SB 86) includes $4.6 billion for districts to address “learning loss related to COVID-19 school closures.” The approaches vary across the state, but the caring, expertise and dedication of educators are constant and inspiring, and the efforts are making a difference.

An oft-cited McKinsey & Co. study from late last year warning that students are between five and nine months behind on average in math due to the pandemic recommends numerous solutions to support students, including high-intensity tutoring, acceleration academies, and reimagining curriculum, teaching, and technological and supporting infrastructures — strategies CTA educators across the state are already leading.

“Learning is happening. Teaching is happening,” says CTA President E. Toby Boyd. “Let’s talk about resilience and recovery support for students that need extra help, and the educators who are leading those efforts!”

Curriculum Review, Summer School

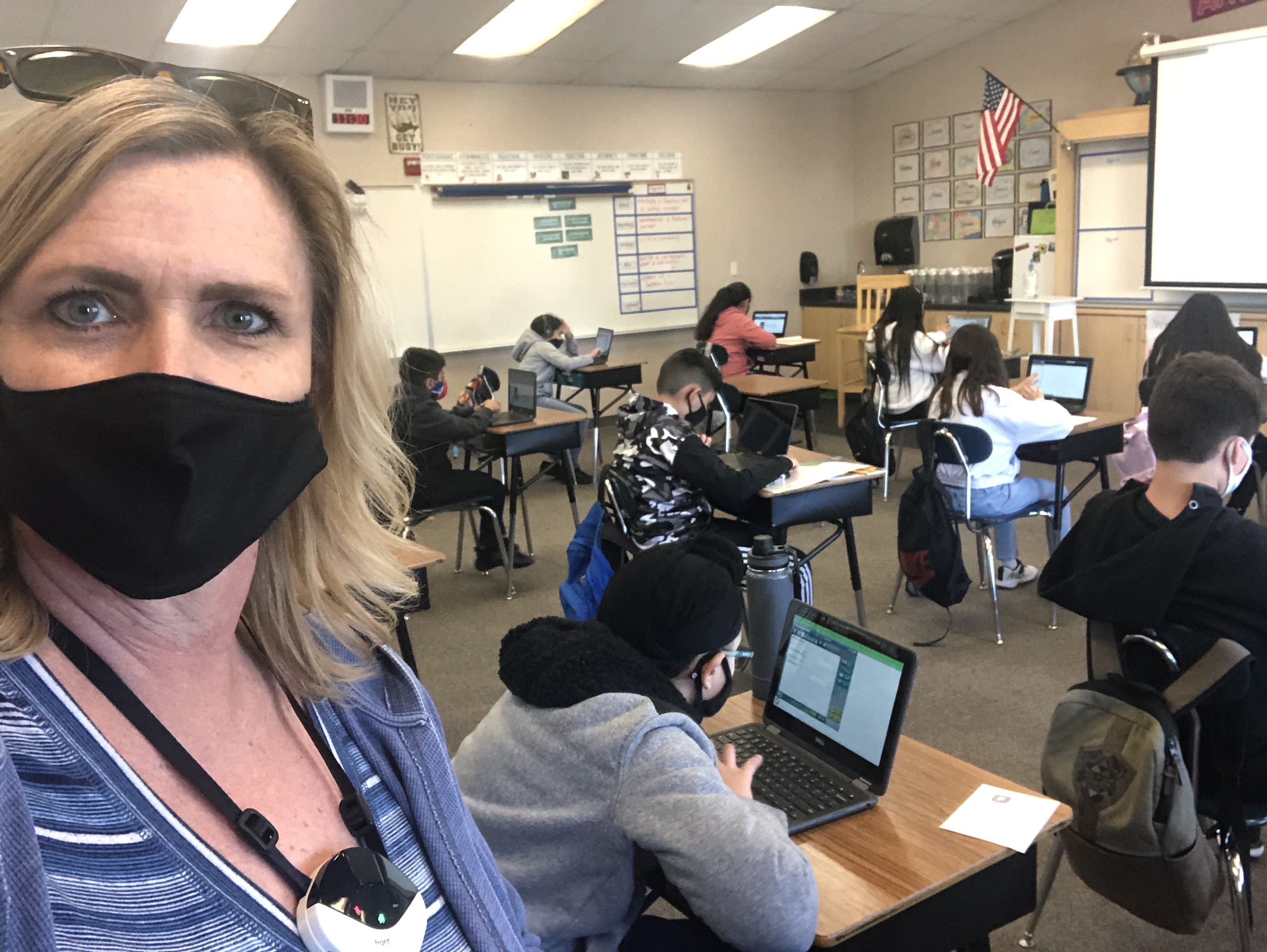

JoDee Bonales in her fifth grade classroom. “We’re focusing on what is most important for students to be prepared for next year.”

“It’s hard to determine where kids are, and there are holes all over the place,” says JoDee Bonales, a fifth grade teacher and president of Ceres Unified Teachers Association. “We’re trying to get a stable environment and then focus on what is most important for them to be prepared for next year.”

When school wound down in crisis distance learning last year, Ceres Unified School District teachers came together to discuss the next school year’s curriculum and potential changes needed. The approach was complicated by changing health conditions, which meant Ceres schools opened the year in distance learning and then shifted to a hybrid model in November.

Bonales says educators met with their colleagues who teach the grades above and below theirs to determine areas students needed more work on, with a keen eye on concepts that are foundational to further learning, such as in math. While reading skills can be taught in other content areas, many math standards require deliberate attention to ensure students are able to move on to more complex lessons.

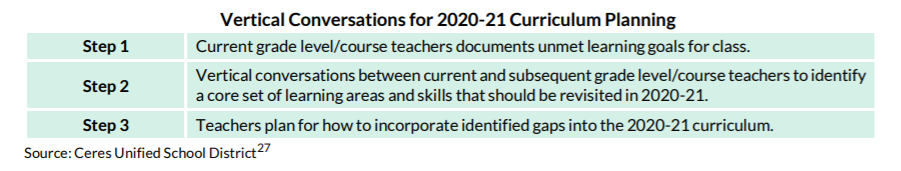

Ceres Unified School District had teachers come together to discuss learning gaps and how to address them.

JoDee Bonales

“We talked about what didn’t get taught last year. All of our sites came together, and it was done by the teachers,” says Bonales of the 730-member local association. “What are the most essential essentials and how can we focus on them? Districts need to allow teachers to make the decisions that are best for their students.”

The approach attracted attention as far away as Ohio, where the Cleveland Metropolitan Schools Learning Loss Toolkit includes the Ceres approach as a case study.

“Teachers are the most knowledgeable of the specific competencies, topics, and skills that students may not have received or mastered … due to school closures,” the report reads.

Students are excited to be back in classrooms together as a community, Bonales says, and educators are hard at work figuring out how to best support their social and emotional needs, so they can learn the academic fundamentals they need to progress. Bonales adds that some students are excelling in the distance environment, and educators need to be mindful of supporting their learning as well.

“Some of my students are thriving, and I don’t want to hold them back,” she says. “The gap is wider than before.”

In the effort to fill that gap, the district is stepping up summer school this year, negotiating increased pay for educators to ensure students have familiar, knowledgeable and experienced support they need.

“The district came to us as a local and said, ‘We want our teachers to teach summer school,’” Bonales says. “I signed up to do it myself.”

Tutoring: Students Are Seen and Heard

United Teachers of Richmond (UTR) member Terra Doby remembers struggling with reading as a young child and how it affected her. She says the experience informs and empowers her work with students who need reading support and with her kindergartners. She participates in the Program for Academic Success, a West Contra Costa Unified School District tutoring program that supports approximately 60 African American students experiencing difficulty with reading literacy.

Terra Doby

Four days a week, Doby works with five second grade students for an hour — a setting that affords the kind of engagement they need to best learn.

“I noticed students were longing for interaction. They were feeling unseen,” says Doby. “Working in small groups is great because they feel seen and heard.”

A January report by the Learning Policy Institute explores the use of high-quality tutoring as an effective intervention strategy to support students during the pandemic, finding that successful tutoring has four main characteristics:

• It employs credentialed educators.

• It is provided at least three days a week for at least 30 minutes, as part of the regular school day, in groups of five or fewer.

• It invests in staff capacity building.

• It builds relationships between students and teachers.

“While much of what has been lost during this pandemic cannot be replaced, a well-designed, well-funded tutoring initiative is one way we can increase instructional time for students and provide instructional support for teachers,” the report reads.

“[Intensive tutoring] empowers students. That’s what keeps them coming back every day.”

—Terra Doby, United Teachers of Richmond

Since Doby works with a vulnerable population of students, she says it’s unclear whether their needs are caused by the pandemic or if it exposed pre-pandemic learning gaps associated with inequality. Either way, Doby’s attention to their social and emotional needs, daily affirmations to support their confidence and self-esteem, and ongoing skills practice to support their reading are making a difference — and they’re having a lot of fun, too.

“They’re eating it up! I’m seeing lots of growth!” says Doby, who drops off materials at her students’ homes, including valentines for all her kindergartners. “It empowers them, and that’s what keeps them coming back every day. Just because you’re a reluctant or non-fluent reader doesn’t mean you can’t learn and grow.”

Doby is one of 10 UTR educators employed by the district for the targeted program, which pays market-rate wages for experienced teachers — a fact that shows the district is invested in the goal of providing resources to students, Doby says.

“This investment will help students grow and thrive.”

Educators Teaching Educators

During the winter surge, Los Angeles County was the global epicenter for COVID-19 spread, with underresourced, primarily Black and brown communities disproportionately impacted. With more than 1.2 million cases and 23,000 deaths countywide, the virus has touched many students and educators alike.

“We tap into different learning needs and include lessons that make students feel seen and valued.”

—Gabriela Orozco Gonzalez, Montebello Teachers Association

Gabriela Gonzalez

“We’re surviving together as a community. We’ve lost a lot,” says Montebello Teachers Association (MTA) member Gabriela Orozco Gonzalez, who not only has eight students who lost a close relative to COVID, but whose own father died from the virus. “We’re in a unique situation as a community. How do we empower students and parents? By being present.”

In Montebello, the path to this support began a few years ago when MTA became the first local association to win contractually protected teacher voice on what kind of professional development educators need to best support Montebello students. Pre-pandemic, teachers teaching teachers had a huge impact, and during distance learning, perhaps even more. The result is a virtual academy coming this summer modeled after CTA’s Good Teaching Conference.

“Teachers in Montebello are looking at education in a unique way, tapping into different learning needs and including lessons that make students feel seen and valued,” Gonzalez says. “How can we tie this into everything we’re doing to target their needs and fill the gap? How can I build community?”

The response was massive, not only from educators who want to attend, but also those who want to lead sessions, with submissions ranging from supporting students during distance learning to educational technology and virtual field trips. Gonzalez says the teaching environment has spurred interest in creative approaches to engagement, with educators taking risks to be lifelong learners for their students.

Patty Domingo

“We all became first-year teachers again because of the pandemic,” says Patty Domingo, MTA member and Teacher on Special Assignment for the district’s Teacher Induction Program. “It pushed us to adapt.”

Teacher and MTA member Myra Pasquier says their approach to professional development is about building community among educators working together to support one another and focus on the unique needs of their students.

Myra Pasquier

“It’s been learning together. We have to find ways for them to collaborate with each other,” Pasquier says of MTA’s 1,200 educators. “It’s been difficult, but I know when we go back it will be different because of what we’ve learned.”

In Richmond, UTR educators are also harnessing the power of professional development to support students through unfamiliar times. Laurie Roberts, a teacher on special assignment, educational technology coach and UTR member, began holding learning sessions on instructional technology for educators last year, as well as office hours to support their new needs. This expanded into full-blown edtech trainings and a question that went out to all educators: What kind of professional development do you need right now?

“We decided to engage teachers the same way they engage students — asking them what they want,” Roberts says. “We’re trying to keep up with what they need, which are skills that will help them help their students.”

Laurie Roberts

Asedo Wilson

And the training isn’t limited to distance learning and tech. UTR educators are engaged in race and equity professional development on a weekly basis, with the understanding that inequities existing long before the pandemic have been exposed and exacerbated, requiring deliberate and continuous work to undo.

“We’re still having conversations about race and equity, because we still have to be on the same page,” says Asedo Wilson, educator and UTR member. “If we can’t address these issues with each other, how can we help our students?”

Unique Needs Will Take Time

Yesenia Guerrero

No matter the approach, when school buildings reopen, students will have a variety of unique needs that educators will have to identify and work to support as we all emerge changed from the pandemic. (See story on school counselors, page 27.)

“Teachers and schools are recognizing that we need to assess each student and meet them where they are,” says special educator Yesenia Guerrero, a member of Lennox Teachers Association. “We’ll need time to fill the gaps, but the kids are very resilient.”

“Learning loss”? No, say educators

Doug Patzkowski

“I think it’s part of the top-down structure of education where corporations determine what students should know, instead of people who have connections with them.”

—Doug Patzkowski, Montebello Teachers Association

“Students aren’t losing anything. They’re learning differently. They’re learning a lot of different skills. It’s not traditional, but they are definitely learning.”

—Yesenia Guerrero, Lennox Teachers Association

“I hate the term, because you learn even when you’re not in class. If you’re going to call it ‘learning loss,’ then it was happening when we were in person.”

—Asedo Wilson, United Teachers of Richmond

“I understand there are students who aren’t able to process this way, so I’m OK with the term, but it negates all the hard work educators are doing. When I hear ‘learning loss,’ it feels like it’s our fault.”

—Terra Doby, United Teachers of Richmond

“‘Learning loss’ puts such a bitter taste in everyone’s mouths and has a negative connotation. We don’t know they have learning loss. It might be curriculum loss.”

—Kirsten Barnes, Hanford Secondary Educators Association

“Our students are learning so many other skills during this time. Their academic tech skills have been growing so much. This year, they’ve become experts on multiple platforms.”

—Myra Pasquier, Montebello Teachers Association

Related Story –

School Counselors: Brokers of Hope

Elvia Estrella

Kirsten Barnes