As the number of students with trauma increases, educators turn to approaches that focus on relationships, empathy

More and more of our children and youth are coping with the impact of traumatic events in their lives — including chronic homelessness and ongoing abuse, the detention or incarceration of a family member, destructive natural disasters, and shootings and other violent acts in communities. Trauma severely affects their ability to learn and grow, and often results in disruptive behaviors.

Our series of stories looks at how educators are handling students with trauma. Many are turning to trauma-informed practices and establishing trauma-sensitive schools to reach these students and help them succeed. We’d love to hear your insights or relevant experience; email editor@cta.org with “trauma” in the subject line.

Contents

Stories

- Teaching Students With Trauma: Practices that work

- A Culture of Compassion: What trauma-sensitive schools look like

- Phoenix Rising: Healing after natural disasters

- Crisis in Our Classrooms: Frightened, anxious immigrant students try to focus on education

- How COVID-19 Impacts the Undocumented

- Returning to Children’s Community Charter School in Paradise

- A Path to the Future: How educators can help

- No Such Thing as a Bad Kid: Youth-care expert Charles D. Appelstein

- Taking Care of You, Too: Educator self-care is critical

- In Their Own Words: Helping students tell what they’ve lived

Resources

- How to help students after disaster

- Restorative practices that aid in trauma recovery

- Trauma Toolkit for Educators

- Helping our immigrant & undocumented students

- Know your rights with ICE

- State of Crisis: Dismantling Student Homelessness in California

- Educator self-care tip sheet

- Defining trauma

- Symptoms of trauma

- Guidance from UC San Francisco’s HEARTS

Teaching Students With Trauma: Practices That Work

Deposit photo

By Sherry Posnick-Goodwin and Katharine Fong

For 20 years, Christa Maldonado thought that students only learned the hard way. When confronted with bad behavior, the social studies teacher and department chair at Valley View High, a continuation school in Ontario, says a punitive response was all she knew.

“I really believed that students only learned from tough consequences,” the Associated Chaffey Teachers member says. “If a student didn’t have punishment, what would stop them from repeating the behavior? Or worse, what would stop the rest of the class from copying that behavior? Without consequences, I would lose all control!”

Then in 2018 Maldonado, together with her principal and school counselor, attended the Trauma-Informed School Conference hosted by the Beyond Consequences Institute in Denver. They were so struck with the practices they learned that they went back and trained their entire staff in a trauma-informed approach to working with students.

“This approach focuses on regulating students’ emotions using science-based solutions rather than focusing on students’ behavior,” Maldonado says. “We realize that behavior is a symptom of a larger problem and that creating a strong relationship with the student is essential to helping them be successful.”

She points, for example, to a classroom student who got “very angry” with her when she asked the girl to stop using inappropriate language. The girl began cursing at Maldonado.

“Before using a trauma-informed approach, I would have removed the student from class for cussing me out, and she would most likely have been suspended. Instead I said, ‘You seem really frustrated this morning, is everything OK?’ She started sobbing: ‘No! I just got these braces and they’re killing me.’ I knew I could address the behavior later, when she was in a better place emotionally. The important thing was to make the emotional connection in the moment. She almost lost her Government class because her teeth hurt.”

For Maldonado, trauma-informed teaching has been a revelation, and she is not alone. Educators across the state and around the country have found that such practices, in conjunction with other approaches such as restorative practices and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, are allowing them to make real connections with students and keep the focus on learning.

For Maldonado, trauma-informed teaching has been a revelation, and she is not alone. Educators across the state and around the country have found that such practices, in conjunction with other approaches such as restorative practices and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, are allowing them to make real connections with students and keep the focus on learning.

“Behavior is a symptom of a larger problem. Creating a strong relationship with the student is essential to helping them be successful.”

– Christa Maldonado

Looking past the behavior

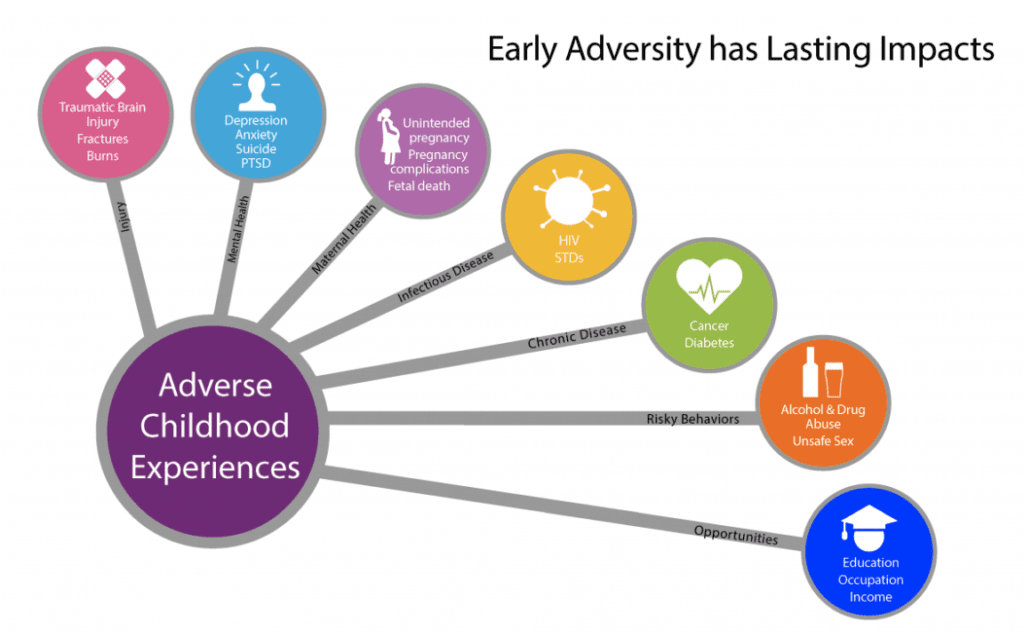

Centers for Disease Control

According to a 2018 report by the Learning Policy Institute, some 46 million children in the United States are annually exposed to violence, crime, abuse, psychological trauma, homelessness or food insecurity. Such adverse childhood experiences are often connected to poor health and educational outcomes. Traumatic stress can affect a student’s ability to learn, function in social environments, or manage emotions and behaviors.

A trauma-informed educator such as Maldonado is more acutely aware of how trauma alters the lens through which its victims see their world and follows practices that help students succeed. Research shows that the effects of trauma can be lessened when students learn in a positive school climate with long-term, stable relationships that support academic and social-emotional development. That in turn leads to an environment conducive to all students’ well-being and growth.

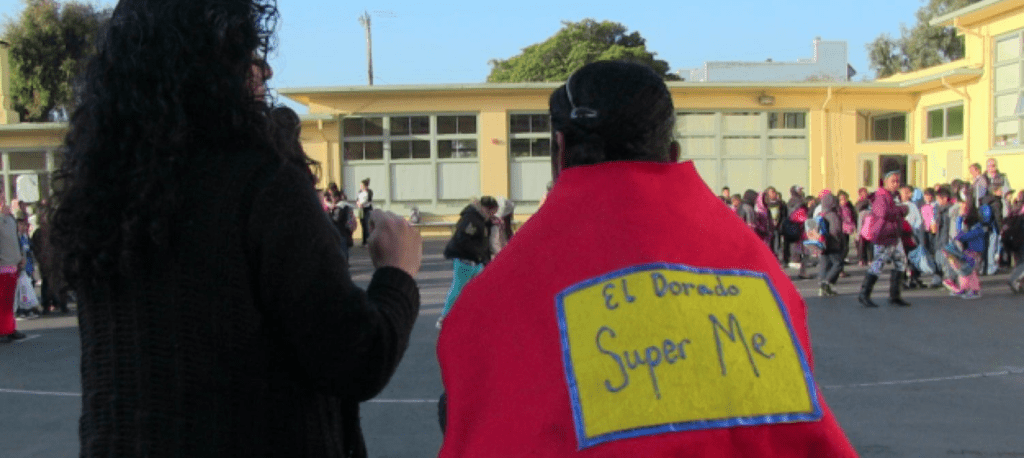

Increasingly, educators, schools and school districts are seeing the value — and results — of trauma-informed practices and trauma-sensitive sites. Anita Parameswaran, who has taught at both El Dorado and Daniel Webster elementary schools in San Francisco, has been an educator for seven years. She says that every year at least a quarter of her students have experienced trauma, from homelessness to witnessing shootings of loved ones to facing deportation.

“Students with trauma may retreat and not speak or open up to anyone. They might exhibit violence like throwing objects or flipping desks. They might threaten anyone who they see could hurt them. They might run away without informing an adult. They might need extra attention at all times,” says Parameswaran, a member of United Educators of San Francisco (UESF).

She and other El Dorado and Webster educators received training in trauma-informed practices from UC San Francisco’s Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS) program, which has had a big impact, according to Parameswaran.

Anita Parameswaran / Scott Buschman

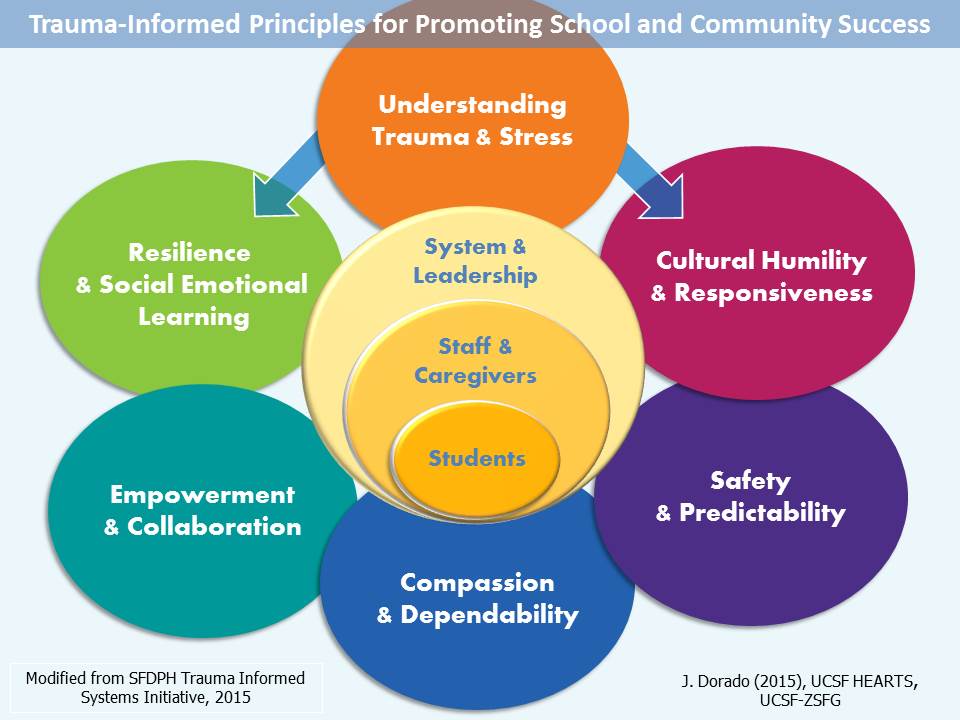

“In order to handle these behaviors, it is important to teach through a trauma lens,” Parameswaran says. “This means understanding what the student has experienced, building a relationship with that student, creating predictability every day, reading body language, giving time and space to self-regulate, incorporating social-emotional learning to develop empathy, and giving positive recognition and reinforcement.”

The HEARTS program, in fact, is guided by these core principles, which promote both school and community success (see diagram below).

Susan Kitchell / Scott Buschman

Susan Kitchell, a school nurse with San Francisco Unified School District, has also received training from the HEARTS program, and has read “voraciously” on trauma-informed practices. She sees the impact of the practices at work.

“Unfortunately, too many of the young people I have been privileged to serve have had experiences that no one should undergo,” says Kitchell, a UESF member. “I have had students come to me for something as simple as a Band-Aid but, with some exploratory interactions, wind up sharing their life experiences.

“Students who feel they are being heard respond well to the adults who are listening. One student at a time, we can create an atmosphere of understanding and acceptance, thereby increasing school attendance and participation in class and school activities.”

Big changes in class

Educators who have been trained in trauma-informed practices are making substantial changes to how they interact with their students. Jennifer Sinclair, a sixth-grade teacher at David Reese Elementary in the Elk Grove Unified School District, also took part in the UCSF HEARTS program and learned more at an Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development annual conference. She says her entire year now starts off differently. “I take much more time building relationships with students and have them learn that our classroom is a safe space,” says Sinclair, an Elk Grove Education Association member.

Jennifer Sinclair

“I have introduced peace corners, which give students a calm area in the room to have a break when they feel themselves about to have a challenging moment. I have peace kits, which include a variety of sensory items that are tools to help them refocus themselves back to learning.”

In addition, Sinclair has implemented structural changes to the school day and week. She opens and closes each day with community circles, where students stand in a circle, and each answers a posted question designed to help them learn to listen and get to know their classmates in a different way.

“We learn that we have more in common with each other than we think, and we can better support each other.”

– Jennifer Sinclair

She also has family meetings, similar to restorative circles, once a week or as needed, where students sit and answer prepared questions that start simple and can become more complex, often leading to emotional moments and discussion. They follow four guidelines:

- Speak from the heart.

- Listen from the heart.

- No need to rehearse.

- Just say enough.

Parameswaran cautions that while trauma-informed practices are very effective, it takes a village. “A teacher singlehandedly cannot teach 22 students when there are seven to 10 students who have suffered high trauma in the classroom,” she says. “It is imperative that the teacher receive the necessary support and manpower — from the principal, behavior coach, social worker, therapist, psychologist and paraprofessionals.”

Trauma: The Facts

Defining Child/Youth Trauma

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network says trauma results when a child/youth feels intensely threatened by an event they are involved in or witness. Events include:

- Bullying

- Community violence (shootings, bombings, or other types of attacks)

- Complex and early childhood trauma (repeated and prolonged exposure to trauma-inducing situations such as abuse, neglect, poverty, etc.)

- Domestic violence

- Disasters

- Refugee trauma

- Traumatic grief

For the full range of events, go to nctsn.org.

Symptoms of Trauma

Educators might observe various behaviors — or changes in behavior — by students who are traumatized, depending on age and type of trauma. These include:

- Anxiety, fear and worry about safety of self and others

- Worry about recurrence or consequences of violence

- Increased distress, irritability

- Decreased attention and/or concentration

- Changes in behavior, such as:

Withdrawal from others or activities

Angry outbursts and/or aggression

Change in academic performance

Absenteeism

Decreased attention and/or concentration

Increase in impulsivity, risk-taking behavior - Difficulty with authority, redirection, or criticism

- Re-experiencing the trauma (e.g., nightmares or disturbing memories during the day)

- Emotional numbing (e.g., seeming to have no feeling about the event)

For the full list, sorted by elementary, middle and high school, go to nctsn.org. Note that teachers are mandated reporters and must report all known or suspected cases of child abuse

or neglect.

Guidance from UC San Francisco’s HEARTS

1 Recognize that a child is going into survival mode and respond in a kind, compassionate way.

Ask yourself, “What’s happening here?” rather than “What’s wrong with this child?” This simple mental switch can help you realize that the student has been triggered into a fear response, which can take many forms.

Reflect back to a student who is acting out — “I see that you’re having trouble with this problem,” or “You seem like you’re getting kind of irritated” — and then offer choices of things the child can do, at least one of which should be appealing to him or her. This will help them gain a sense of control and agency and feel safe. Over time, if a student with trauma sees that you really care and understand, they will be more likely to say, “I need help.”

2 Create calm, predictable transitions.

Transitions between activities can easily trigger a student into survival mode. That feeling of “Uh-oh, what’s going to happen next?” can be highly associated with a situation at home where a child’s happy, loving daddy can, without warning, turn into a monster after he’s had too much to drink.

Some teachers will play music or ring a meditation bell or blow a harmonica to signal it’s time to transition. The important thing is to build a routine around transitions so that children know what the transition is going to look like, what they’re supposed to be doing, and what’s next.

3 Praise publicly and criticize privately.

For children who have experienced complex trauma, getting in trouble can sometimes mean either they or a parent will get hit. And for others, “I made a mistake” can mean “I’m entirely unlovable.” Hence, teachers need to be particularly sensitive when reprimanding these students.

4 Adapt your classroom’s mindfulness practice.

Mindfulness is a fabulous tool for counteracting the impact of trauma. However, it can also be threatening for children who have experienced trauma. Consider using these adaptations:

Tell students that, if they wish, they can close their eyes at the beginning of the practice. Otherwise, they should look at a spot in front of them so no one feels stared at.

Instead of focusing on how the body feels, have students focus on a ball or other object they’re holding in their hands — what it feels like and looks like in their palm.

Focus on the sounds in the room or of cars passing outside the classroom — something external to the body.

5 Take care of yourself.

This actually should be number one! The metaphor of putting on your own oxygen mask first before putting it on the child is very true in this situation.

See hearts.ucsf.edu for more about the HEARTS program. Adapted from Greater Good Magazine, 2013.